|

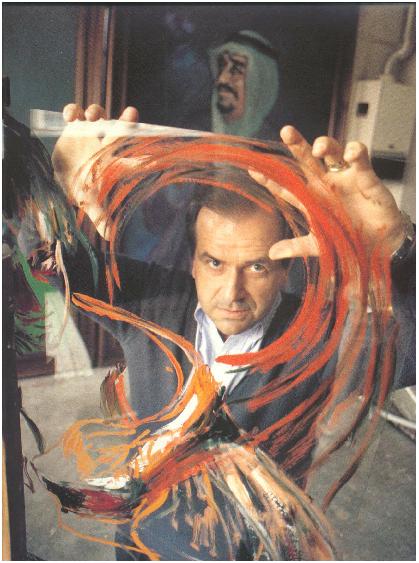

| Dogs 2009 Nicola Samori (via Art Lab) |

My work remains representational. The paintings I look at reflect ideas that I haven't figured out how to articulate. I recently noticed these images are missing a common piece: traditional narrative. By that I mean they aren't about the figures or objects in them at all and instead are about relationships with painting and perhaps even more vague ideas. They are stripped of narrative.

|

| J.V. 2008 Nicola Samori (via Art Lab) |

Both

Nicola Samori and

Alex Kanevsky paint the figure. The

way each paints is louder than the figures themselves.

Nicola Samori suggests features of the face or the shape of a head using a rich, Rembrandt-gray palette. But in the same image, that language is twisted and manipulated, until perhaps those colors become other shapes entirely. This creates an unsettling reversal of abstract marks that first articulate something recognizable and secondly become marks themselves.

White Samori's figures are painted in an ambiguous space, Alex Kanevsky's figures interact in clearer rooms and bathtubs. But beyond those interiors, a traditional narrative seems absent. Of course, like Samori's, the figures are

doing something. Kanevsky's might be washing their face or bent awkwardly in the tub. But there never is any direction here. Instead what comes alive is Kanevsky's sensational mark making, the bright colors and melted swatches. These are painted mostly on Durlar.

When I showed Kanevsky's work to a friend about two years ago, he didn't like them. He thought they were sterile. And in fact, he's right. The backgrounds or the furniture these figures interact with don't tell us any more about how we should be interpreting this image. They tell us how beautiful these pastel colors or a shadow under a nose are in their own right.

To further the point, I'll take a leap here and mention the popular show

Mad Men. I am currently enjoying the second season. But I'm always left feeling something is missing - the same something that I oppositely found in a show like

The Wire: better writing - or, another words, narration.

David Mendelsohn of the

New York Review of Books gives the show a thrashing. His critique, which first ruined the show for me, later helped me understand why I also enjoy it so much: it's painterly. It shares the same ideas I am exploring and looking at with respect to the mentioned artists: figurative paintings without narrative.

Mendelsohn says, "Most of the show's flaws can, in fact, be attributed to the way it waves certain flags in your face and leaves things at that, without serious thought about dramatic appropriateness or textured characterization". The same argument can be applied to the paintings mentioned. Cues are used, faces warped or figures with their back turned - but ultimately there isn't much to be solved there. Like

Mad Men does, these paintings want us to recognize the whole image as a shape, as an object - as a point of narrative against

other objects.

Like the critique of

Mad Men, these paintings dance around the surface of traditional narration, presenting textures, colors and emotional playfulness that coalesce into something recognizable but result only in becoming a graphic of itself and how it's made, resulting in a narrative that is more abstract and ambiguous.